The Left Behind by Robert Wuthnow is one of several books about rural culture that I read upon the advice of my publisher, Wise Ink Media, Minneapolis, as we began to consider where my book might fit, say, in the literal or figurative book shelves of the world. According to the Princeton University Sociology Department website, “Robert Wuthnow is Professor of Sociology Emeritus and former director of the Princeton University Center for the Study of Religion. He is the author of more than three dozen books and numerous articles about religion, civil society, communities, and American culture.” Credentials.

Before I continue further with The Left Behind, I want to also recommend Heartland by Sara Smarsh and Uprooted by Grace Olmstead to anyone who is curious enough to look beyond the stereotypes of small town and rural American culture. That’s where I grew up, too, and it’s where I spent the best part of my professional life, as a high school English teacher at New Prairie High School, New Carlisle, Indiana.

I didn’t begin reading The Left Behind until after I had nearly finished writing When Once Destroyed. What I discovered in Dr. Wuthnow’s book was an affirmation of my own insights in the story of my father’s life and in the destruction of his community.

Wuthnow acknowledges the resentment I feel about attitudes directed at people in rural communities that are, by the way, mirrored in attitudes directed toward people in my chosen profession; that is, that the only people who live in rural communities or teach K-12 are people who couldn’t escape to something better. While it would be an oversimplification to ignore other factors, I sense that the declines in support for public education and in respect for rural communities are connected to the cultural diminishment of the people who live and work in those circles. Micro-dehumanization.

Wuthnow writes, “For more than a century New York Times editorials had vacillated between romanticized essays about the rustic life and caustic criticisms of backward voters in rural areas who were intent on impeding urban progress”(2-3).

When it came to what I learned about the Upper Wabash Valley Flood Control Project in research for my book, I found that to be true in the Wabash Plain Dealer and the Indianapolis Star, as well. There, the romanticized think pieces come after authority’s more subtle criticisms had already made a particular rustic life safely impossible.

It isn’t only the machinations of people in power that are familiar, though. The characterizations of opponents of “development” as ignorant troublemakers also ring a bell. Also, we can see that “Voting against their own interests,”(3) as we hear they do, really means voting against what everyone else says are “their own” interests. It isn’t only about small town and rural residents, is it? It’s what happens when people lacking power are pitted against those who have it.

Watch your town or watch your neighborhood destroyed for a “greater good” and then hear, “Why don’t you say, ‘Thank you.’”

Wuthnow moves me to look beyond the resentment, though, because resentment succumbs to a “nothing we coulda done” historical inevitability. Does my book move beyond resentment? He made me wonder.

“Understanding rural America requires seeing the places in which its residents live as moral communities” (4), Wuthnow writes.

Okay, good, I did that. I’ve portrayed the neighborliness that comes from the strong principled underpinnings of people like my father and people like educator Cliff Funderburg, the most vociferous opponent of a congressman, a bogus state of Indiana commission and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The immorality, I found, came from salesmen on the other side. And, it isn’t only applicable to rural areas. It’s Robert Moses in New York at exactly the same time. It’s Bernie Sanders versus Elon Musk, today. It’s everywhere that genuine values are expendable. Where graves are defiled.

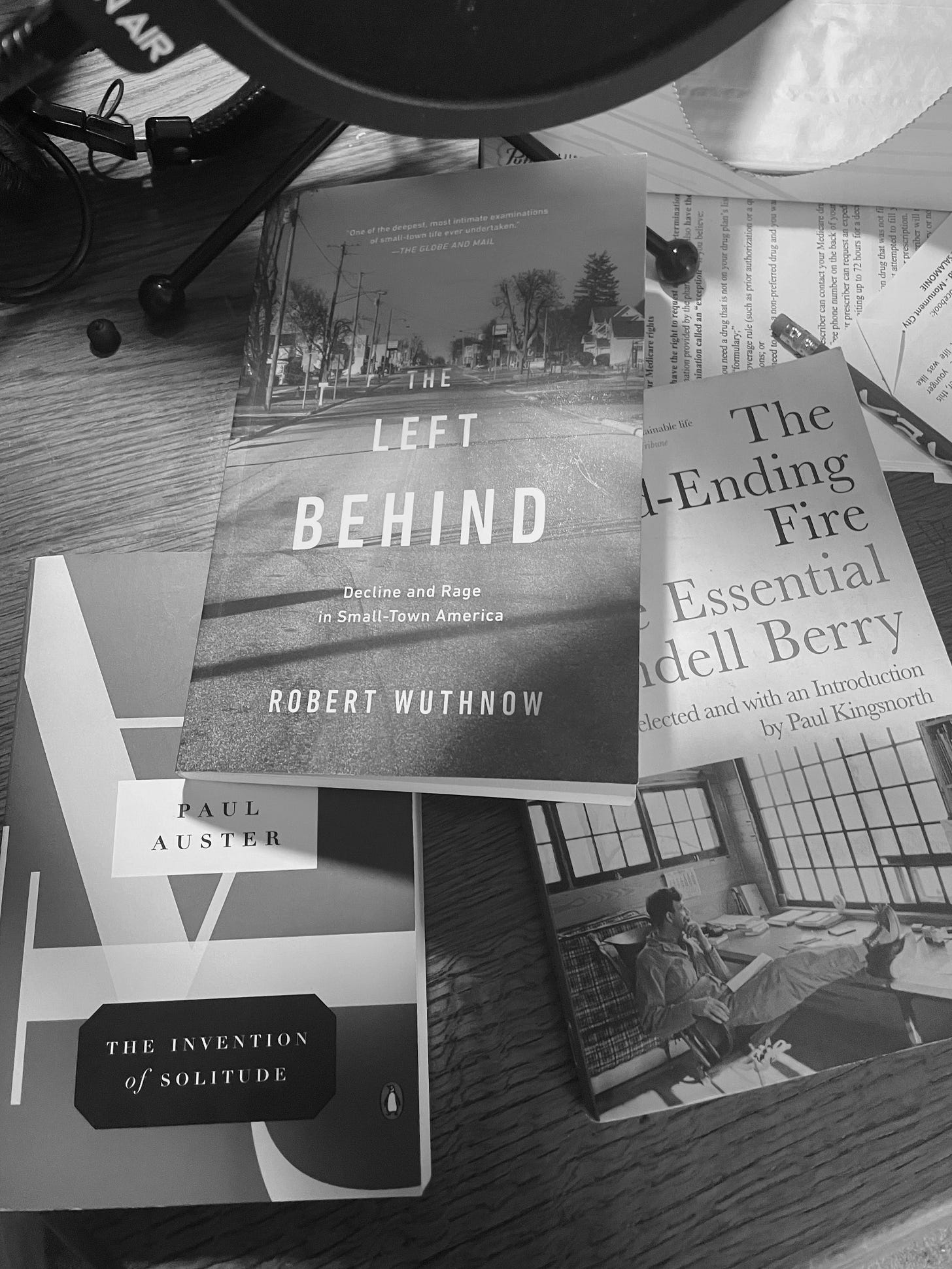

This brings me to Wendell Berry’s 1978 essay called, “Horse Drawn Tools and the Doctrine of Labor Saving,” that I found in The World Ending Fire The Essential Wendell Berry anthology. “It appears that we abandoned ourselves unquestioningly to a course of technological evolution, which would value the development of machines far above the development of people” (154-5).

“Suppose,” Berry continues, in 1945, “we had really tried to live by the traditional values to which we gave lip service” (155).

My father lived by those values. Me, not so much. For me, I fear those values are nostalgia, “romanticized essays about the rustic life.’

In the months before I began writing When Once Destroyed, I began on impulse reading Berry, whose familiar voice was that of a community I had nearly forgotten I belong to, that of my father. As I began writing, with a recommendation to read Paul Auster from University of Notre Dame English Professor Emeritus Stephen Fredman, I was in the midst of reading Auster’s The Invention of Solitude, a son’s story of his father. “If I do not act quickly, his entire life will vanish along with him,” (4) Auster wrote. And, “He who sees everything might read in any body what is happening anywhere, and even what has happened or will happen. (161)”

Inside the back cover, after my first read, I’ve written, “I wanted to do right by my dad and he didn’t have to spend a lot of time telling me what that was. I could tell by watching him.”

“I want to tell my grandson about my dad,” was all I needed. For what I wrote, what seemed to matter was enough.

Please look for When Once Destroyed at booksellers later this year.